What can be heard in music?

Christopher Peacocke explains

what , why, and how

How come we hear things in music? Why does it make a difference to see the performer instead of just listening to a piece of music? And why is it that accompanying a text with music can make its effect more powerful? We normally accept all these features of music without giving them a second thought but, if we pause and think about them, we are suddenly at a loss. After all, music is technically just a series of sounds; how can it not only provoke emotional reactions but also express emotions themselves? Music is about sounds; what difference could it make to see the performer? And how can music tell us stories?

It seems that music is a mystery. Our everyday experiences no longer make sense when we look at them too closely. Thankfully for us, Christopher Peacocke, professor of philosophy at Columbia University has some answers. Guest lecturer for a cycle of conferences at College de France, Christopher Peacocke discusses “The Soul in Sound.” In two lectures, he tells us what can be heard in music, why, and how. Let’s go through his first lecture and explore these questions.

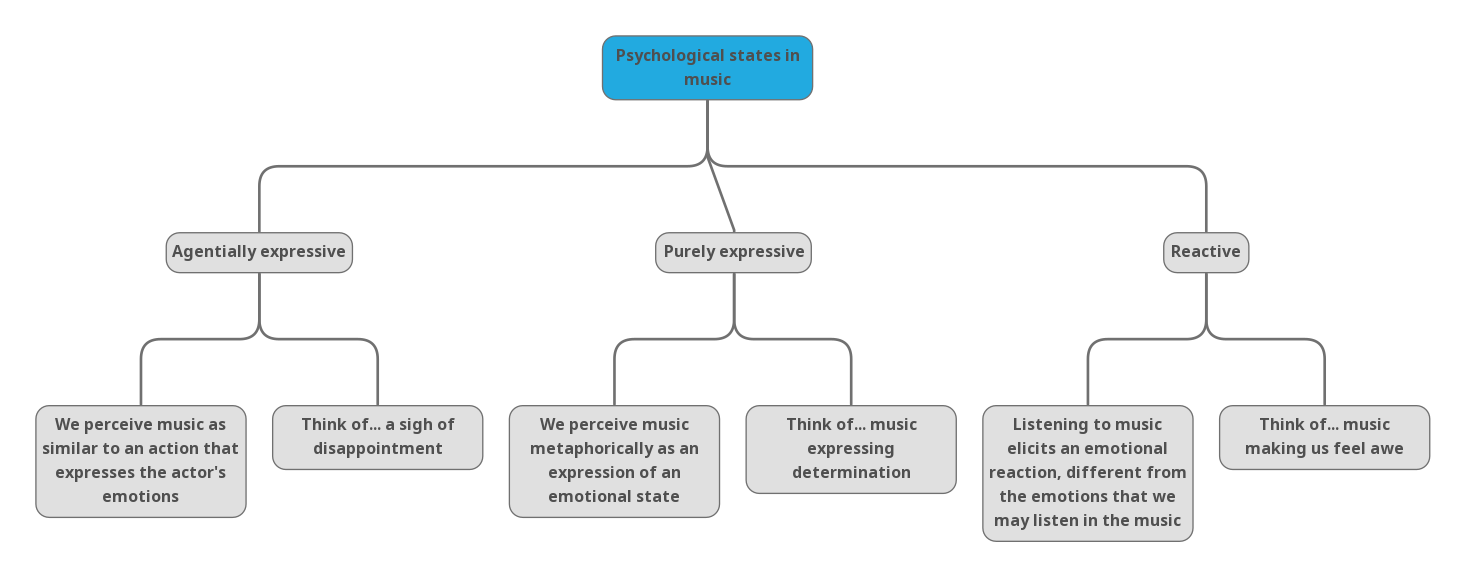

What psychological states can be heard in music?

Performed music is first and foremost an action. Unlike listening to random sounds – the buzz of an air conditioner, or even the sound of waves crashing on a beach – when we listen to a piece of music that is performed, we experience it as an action of the musical performer. But there’s more to the story. According to Peacocke, we perceive music as not only a series of sounds but also as the expression of a broad range of psychological states. Moreover – and that’s the object of Peacocke’s second lecture – we perceive music as the exercise of agency. But what kinds of psychological states are involved in our perception of music?

Agentially Expressive

First, we may perceive music as an action that expresses a certain emotion. In a piece of music, we can hear sarcasm, or aggression, or laughter. Listen, for example, to Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question. Doesn’t the trumpet music sound as questioning what is going on? Or, to turn to a more contemporary example, listen to Radiohead’s song Let Down in which we can hear, unsurprisingly, a sigh of disappointment. Peacocke calls this first case of hearing a psychological state in the music as “agentially expressive.” To put it simply, the music expresses the action of a person, the agent.

Charles Ives, The unanswered question

Radiohead, Let Down

Purely expressive

There is a second case of hearing psychological states in music, but this time without hearing them as the expression of the mental state of an agent. Peacock calls this case “purely expressive.” Here, we don’t hear music as an action that expresses an emotion. What we hear is not an action, but an emotion itself, or a psychological mood, such as determination or weakness. An extremely well-known example can be found in Beethoven, 5th Symphony. Here, music can be heard as an expression of the determination to overcome difficulties.

Beethoven, 5th Symphony

Reactive

There is yet a third psychological state involved in our experience of music, and it reflects our own reaction to what we hear. As Peacocke remarks, we can hear music as terrifying, or awesome, even though the music itself may not express terror or awe. The example that Peacocke gives is Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Peacocke suggests that we do not fully appreciate this piece, unless we are struck by awe, or even terror, for the primitive, non-rational forces of nature and their effects. Here we have to pay attention: it is not that the music expresses terror (as is the case, for example, in Psycho’s famous bath scene music). Instead, in hearing the music we, the audience, are stricken by terror for what is going on. This is why Peacocke calls this third case “reactive.”

Stravinsky, Rite of Spring

Theme from Psycho

Agentially expressive & purely expressive cases

In the case of hearing music as agentially expressive, what happens is that we experience music as similar to an action that expresses the emotions of its agent. Music can be heard, for example, as similar to a sigh of relief or disappointment. So, Peacocke tells us, there are limits to what we can hear in the agentially expressive case. Through an expressive action, an agent can express her mental state; she cannot express, for example, her sense of green, or her taste of banana. Moreover, since they express an agent’s emotional state in action, we cannot understand expressive actions as the outcome of reasoning, or of a calculation of the necessary means to achieve a goal. The explanation of expressive actions lies in the agent’s emotions. Still, they are not completely out of the agent’s control; after all, we may not be able to control how we feel, but we can still control how we express what we feel.

The purely expressive cases are philosophically much more interesting, and Peacocke dedicates to them the larger part of his lecture. Here, we hear some features in the music not as similar to, but metaphorically as something else. It’s not that the music resembles, for example, determination - what does determination sound like, for music to resemble it? Instead, we perceive music as a metaphor for determination. If determination were music, we think, it would sound like that.

How can we hear something metaphorically as something else? Peacocke suggests that this is part of a more general human capacity, the capacity to represent something metaphorically. Apart from the capacity to experience things metaphorically, we also have the capacity to imagine them metaphorically (as we do, for example, when we imagine the nucleus of an atom and the electrons around it as the sun and the planets of the solar system). We can also think of things metaphorically as something else (the Shakespearean scene of Romeo thinking of Juliette as the sun comes to mind). So for Peacocke, metaphor is not fundamentally linguistic – on the contrary, metaphor in language exists only because we need to express in words this phenomenon of representing something as something else. Moreover, Peacocke denies that there are things that can be expressed only metaphorically. Whenever we talk about something being a metaphor for something else, he suggests, what we do is to express it in non-metaphorical terms. In the case of music, when we say that we are hearing a piece as joyful, we are speaking literally. What is heard in music metaphorically can be expressed and communicated in non-metaphorical terms.

We experience what, exactly?

But what is it that we experience in music, when we hear for example nostalgia, serenity, or determination? We don’t experience the concept of nostalgia. We don’t even need to know that concept to hear it in music, as we don’t need to know it to feel nostalgia. Neither do we experience nostalgia itself; we can hear nostalgia in the music without feeling nostalgic at all. The question becomes more puzzling when we realize that in the music, we don’t simply hear a state, such as nostalgia. We feel some particular kind of nostalgia, be it gentle or intense. How is this possible?

To answer, Peacocke suggests that we can recreate in our minds emotions and mental states that we have experienced in the past. Think of nostalgia: we can mentally recreate the experience of feeling nostalgic, without being nostalgic ourselves, as long as we have felt nostalgia in the past. It is in the same way that we can hear something in the music metaphorically as nostalgia. This does not require an ability to define nostalgia as a concept. What is required is our own emotional experience.

The fact that we can hear not simply mental states in general, but specific kinds of mental states (eg. acute or mild nostalgia) vests music with a characteristic specificity. Peacocke refers to this as “Mendelssohnian” specificity, alluding to Felix Mendelssohn’s famous statement when asked about his Song without words:

“The thoughts that are expressed to me by music that I love are not too indefinite to be put into words, but on the contrary, too definite […]. Only the song can say the same thing, can arouse the same feelings in one person as in another, a feeling that is not expressed, however, by the same words.”

Mendelssohn, Lieder ohne Worte

Because of its “Mendelssohnian” specificity, music has a “two-way independence” from any text: the same piece of music can be suitable for expressing different texts; simultaneously, any text can be expressed through multiple alternative musical pieces.

We now understand why accompanying a text with music adds so much to the experience. Since a text can be read in many different ways, adding music makes its meaning much more specific, and therefore more powerful. This is particularly true for emotions and psychological states, which are often left unanswered in text. Music guides the listener through the text, making its content more accessible and illuminating hidden potential meanings. To add a contemporary example to the ones employed by Peacocke: listen to Iron Maiden’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The music added to an 18th century poem about a cursed mariner who lived to tell his story illuminates hidden or ambiguous aspects of the text. Through the music, we hear excitement, death, despair and hope, and the text gains in concreteness and power.

Iron Maiden, The Rome of the Ancient Mariner

We can now also answer whether it is possible to express music in words. As Peacocke remarks, it depends on what we mean by “expressing music in words.” Because of the higher specificity of music in relation to words, what can be heard in music can never be fully described. Moreover, some of the things expressed in music can only ever be understood by those who have experienced them in the past. But this does not mean that there is anything intrinsically problematic in trying to describe a musical experience in words. Hearing music as similar to, or metaphorically as something else means that what we can hear in music can always also be experienced in some other way.

Theories that take music to express some experience that defies any intellectual engagement – and any linguistic expression – are for Peacocke incomprehensible. As he points out, this is precisely the reason why we value music.

Reactive states

The third kind of psychological state that is involved when we hear some music is the reactive. This, as we said, refers to our emotional reaction to what we hear. We can relate our emotional reaction to music to our emotional reaction to other genres, such as films, dramas, or novels. For example, after a good performance of Così fan tutte, we may feel empathy; we may get the same feeling by reading a book or watching a film. But there are two important differences that make music unique and distinct from the non-musical genres.

First, our emotional reactions to music can be provoked even in the case of music unaccompanied by any supportive textual description. Not being linked to any text, absolute music has a generality that words preclude. The second difference applies to cases when there is some supportive textual complement. We said that in music, we hear states and emotions that we are already acquainted with. This means that, when listening to a song, the emotion is given to us in a way that makes us already acquainted firsthand with the experience that is expressed through the music. This creates a connection that language by itself cannot create. That is why listening, for example, to the Countess’ pained aria Porgi amor in the Marriage of Figaro has such a strong effect; the pain in the Countess’ voice resonates with our own, personal experiences of heartbreak. No matter how great it is, a text cannot generate this reaction by itself. This is why opera has, for Peacocke, such a strong emotional effect.

Porgi amor (Le Nozze di Figarro)

So music can express actions that reveal an agent’s emotions. It can also express emotions and psychological states themselves, and it can elicit emotional reactions to its listeners. But more importantly, it tells us something about ourselves. It helps us understand our own experienced emotions better, and it reflects our own emotional development. Maybe that’s why people turn to music when they’re happy, and they do the same when they’re sad. Knowing what can be heard in music is the first step. The next question, that only we can answer for ourselves is to find out, every time, what we do hear in music and how it resonates with us. And through this, to discover our own emotional world.

Further resources:

Listen here to Peacocke’s lecture on What can be heard in the music: https://www.college-de-france.fr/site/en-francois-recanati/guestlecturer-2021-05-05-16h00.htm