The Good, the Mad, and the Ugly part 2

The Critique of Psychiatry

Foucault, Michel Foucault. He was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century and still is in the 21st century. He had a longstanding interest in the interactions between social norms, scientific practices, and political institutions. He dedicated quite some time to the topic of madness in works such as The Birth of the Clinic and Madness and Civilization. He also focused on madness during some of his Lectures at the Collège de France, an important research centre in Paris. He was particularly interested in the relationship between medical practices, authority, and power. And he was also an influential figure within circles critical of psychiatry.

There were many ‘anti-psychiatry’ movements in the 1960’s that raised questions regarding the scientific basis of psychiatry and the way it was mobilized to pathologize political opposition. That is to say, the way in which people with dissenting political opinions were understood to hold their opinions as a result of certain medical problems.

Public discourse is saturated with politicians and pundits taking cheap shots at their political adversaries using clinical categories. Political opposition is described as narcissistic, hysterical, delusional, or some combination of these. It is a classical rhetorical device to present oneself as having a firm grasp on the matter as opposed to the naive, or even delusional understanding of your opponents.

It was Foucault’s contention that psychiatric institutions themselves were not merely neutral medical organizations but also had ulterior political motives. Were the clinical categories that psychiatrists proposed actual medical diseases? Or did they rest on problematic assumptions and were they distorted by all kinds of social prejudice? Some had the idea to abandon the established psychiatric institutions altogether and advocated for patients to band together to form self-empowerment groups that would try to overcome their problems collectively.

It was Foucault’s contention that psychiatric institutions themselves were not merely neutral medical organizations but also had ulterior political motives

Many anti-psychiatry movements were critical of the doctor-patient hierarchy wherein the doctor is the one who knows and the patient is merely a passive object to be studied by the doctor. They looked towards a more democratic form of therapy. Foucault was influential within these circles.

Foucault emphasized that science was not merely an observation of the world as it is. Rather, it approached the world by making theoretical assumptions. Moreover, these assumptions were influenced by social prejudices. Foucault’s argument resonated well with anti-psychiatry circles. The doctor does not merely observe and examine the patient in a neutral and objective manner. The observations that the doctor makes about the patient, that patient being the doctor’s object of study, are influenced by theoretical assumptions, which are in turn influenced by social prejudices. The doctor views the patient through a particular lens or filter, they rely on certain assumptions that are not simply the product of neutral empirical observation.

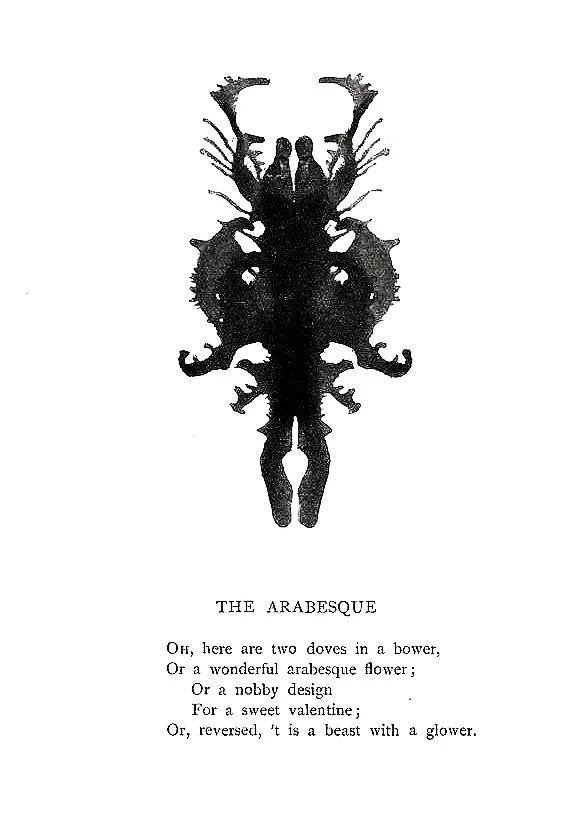

How do we see things around us?

The Influence of History

Foucault argued that there is always a historical filter between us and the world. The way we understand ourselves and the world around us is always influenced by the historical period in which we live, and the society from which we stem. We can compare this historical filter to a pair of sunglasses that you must wear in order not to be blinded by the world around you. These sunglasses alter the way in which we see the world.

It may be common to imagine ourselves as directly experiencing the world as it is when we aren’t wearing any glasses. Foucault’s point would be that we are (metaphorically) always wearing glasses. We either keep our glasses on or we can exchange them for another pair. But there is no direct experience of the world. Our experience is always altered by the way in which our glasses, literally ‘frames’, frame the world. Just like frames change the way in which we see things, so theoretical frameworks change the way in which we see things.

All of Foucault’s work would be shaped by this critical relationship to the historical character of all thought and experience. In his studies on madness, Focault would examine multiple ways in which history interacted with madness. He investigated how social prejudices shaped the way in which certain groups were considered to be mad. He would look at the historical function of institutions that had the power to ascribe madness to certain people, such as the asylum, and examine where they derived their authority from, and how their power functioned socially.

The Critical Perspective

Let us take the asylum as our example. There was a big shift

that occurred in psychiatric practice beginning in the late 18th century. Remember Pinel, the 18th century physician who was an important force in the ‘moral reform’ of psychiatric treatment? Foucault was skeptical of him. The moral reform in psychiatry is traditionally represented through the image of Pinel freeing the mad from their chains. He liberates them from the brutish practices they were subject to in the past. This marks an important step in the development of modern psychiatry. He talks to the mad, reasons with them, and tries to cultivate them morally.

There is truth to this. Even though the use of force was not at all abandoned, psychiatric practice did become less physically violent. However, Foucault is skeptical of the idea that the moral reform is simply a positive development. He rejects the idea that psychiatry simply progresses from its archaic, brutal, and primitive forms, to its modern, emancipatory, and scientific form. Whilst Pinel may be freeing patients from their physical shackles, Foucault is of the opinion that he did so at the cost of constraining them both morally and mentally.

A statue of Philippe Pinel in Paris, in his right hand he holds the shackles he has removed from his patients

Back in the 17th century, the French philosopher Descartes, amongst others, conceived of madness as a form of cognitive error resulting from brain damage. He gives the example of people who believe that they are made of glass, or paupers who believe themselves to be kings. In the early 19th century madness was still associated with believing oneself to be king. However, this came to mean something very different. The psychiatrists of this time came to associate madness with arrogance. If we take a closer look at Pinel and other important figures associated with the moral reform such as Esquirol (Pinel’s student) and Fodéré, some of their ideas may strike as somewhat… sinister.

Madness was related to moral failure. The mad came to be understood as stubborn people who thought they were better than everyone else. This is how ‘taking oneself to be king’ was reinterpreted. It doesn’t matter whether the madman takes themselves to be king or believes themselves to be a social outcast that everyone hates. In both cases, the madman takes himself to be king insofar that he holds fast to his own beliefs against the psychiatric institution and the doctors who lead them. The actual content of their delusional beliefs does not matter. It is their obstinance, interpreted by the doctors as a form of arrogance, that is the problem.

A shift thus occurs between the 17th and 19th century, from understanding madness as a cognitive error (cfr. Descartes) to understanding it as a form of moral deviance. The mad believe themselves to be kings so long as they believe they have the right to define who they are independent of those around them. To address this ‘problem’, the first step of the therapeutic process was to break apart the patient’s beliefs, to grind them down, and force them into submission to their superiors. Pinel understands the treatment of the mad to be “the art of, as it were, subjugating and taming the lunatic by making him strictly dependent on a man who, by his physical and moral qualities, is able to exercise an irresistible influence on him and alter the chain of his ideas”.

A shift thus occurs between the 17th and 19th century, from understanding madness as a cognitive error (cfr. Descartes) to understand it as a form of moral deviance

Therapeutic practice involves breaking down the self-declared kingship of the mad patient. It involves subduing them and grinding them down until they willingly subject themselves to the power of those around them. It is in light of passages such as the above that Foucault came to see the asylum as a battlefield, a play of power in which the doctor tries to force the patient into submission.

Perhaps the mad were inappropriately demonized?

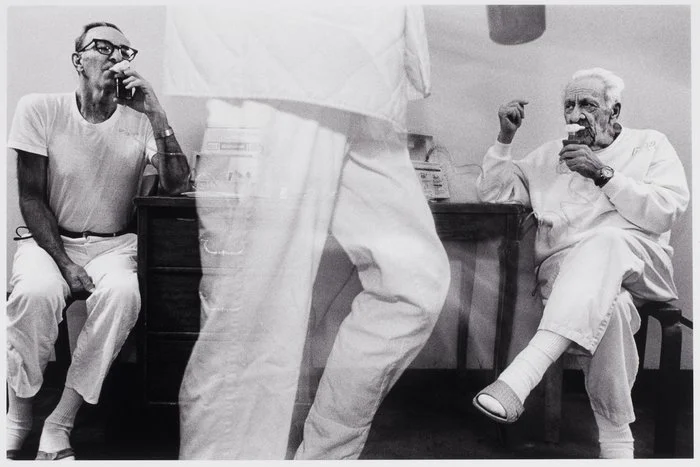

Esquirol’s ideal doctor seems to resemble the perfection of ancient Greek statues. He writes that: “one of the first conditions of success in our profession is a fine, that is to say noble and manly physique; it is especially indispensable for impressing the mad. Dark hair, or hair whitened by age, lively eyes, a proud bearing, limbs and chest announcing strength and health, prominent features, and a strong and expressive voice are the forms that generally have a great effect on individuals who think they are superior to everyone else”. Think of the ideal psychiatrist as a dark-haired version of Achilles (Brad Pitt) in the film Troy.

In between the doctor and the patient were the supervisors. These were servants who ostensibly served the patient but were most importantly relays of information to the doctor, and apparatus to enforce the meticulous regulation of the asylum. Like Achilles, these supervisors ideally resembled the Greek heroes of old, and were supposed to command respect over the patients. “In a supervisor of the insane it is necessary to look for a well proportioned physical stature, strong and vigorous muscles, a proud and intrepid bearing for certain occasions, a voice with a striking tone when needed”.

Re-evaluating the so-called ‘moral reform’ in Psychiatry

Instead of the famous images of Pinel at the Bicêtre and the Pitié-Salpêtrière freeing the mad from their chains, Foucault takes the treatment of King George III, as described by Pinel, as the proper key to understanding the moral reform in psychiatry.

Pinel described the treatment of King George III by Francis willis as follows: “A monarch falls into a mania, and in order to make his cure more speedy and secure [...] all trappings of royalty having disappeared, the madman, separated from his family and his usual surroundings, is consigned to an isolated palace, and he is confined alone in a room whose tiled floor and walls are covered with matting so that he cannot harm himself. The person directing the treatment tells him that he is no longer sovereign, but that he must henceforth be obedient and submissive. Two of his old pages, of Herculean stature, are charged with looking after his needs and providing him with all the services his condition requires, but also with convincing him that he is entirely subordinate to them and must now obey them. They keep watch over him in calm silence, but take every opportunity to make him aware of how much stronger than him they are."

King George III was an actual king struggling from mental distress, most likely what we would now refer to as bipolar disorder. His eventual treatment involved stripping away everything which tied him to his kingship. Deprived of his royal insignia he was isolated in a padded room that was cut off from the outside world. Here, reduced to the status of a caged animal, his cure was to begin. His sovereignty had to be taken away from him. He had to subject himself to a new sovereign, the doctor, so that he could be cured.

The treatment of King George III is the image that encapsulates the logic of the asylum for Foucault. Patients were to be isolated from the external world and, stripped of their power, they would be forced into submission. Afterwards, they could be disciplined and educated, they could be taught the ‘proper’ moral values to adapt to society. Foucault puts a sinister twist on the so-called moral reform. The moral reform involves the moralization of what was previously merely an involuntary cognitive deficit. This moralization, whilst breaking the physical chains that tied the mad down, chained them mentally and morally.

In part one, we saw that Hegel thought that the mad recognized their dependence on rational people. But here the story gets a bit darker. Foucault’s contention is that the mad are forced into dependence upon the psychiatric institution, and ‘the rational people’. Psychiatric staff were meticulously chosen so as to make the mad feel inferior, physically, morally, and mentally. It was the role of the psychiatrist to break these patients down and rebuild them according to proper social mores.

Foucault sees this logic of breaking down the patient’s will and reshaping it according to that of the psychiatrist (who functions to safeguard the public order) as tied to a broader social logic that extends beyond the asylum. He argued that other institutions which might appear benign at first sight, participated in this logic. He raised questions about the ways in which schools and prisons were structured. He saw these institutions as embedded within a ‘punitive society’, a society that rests upon practices of incarceration and the meticulous regulation of daily life to shape socially conforming individuals.

Institutions would filter out individuals who transgress social norms to reform their deviant behaviour. The mad and other ‘deviants’ such as criminals, prostitutes, and the unemployed were seen to be morally depraved social nuisance. They had to be controlled, incorporated, and disciplined within institutions that regulate their behaviour and transform them into ‘proper’ moral citizens. The goal was to make them willingly submit to self-reform, to internalize the values of the people who were given the power to subjugate them, and who allegedly represented the voice of reason.